Our (Students') Work (and Play) Can Make Us Smarter Next Time

Donna Qualley & Matthew Sorlien

We can only be smarter next time, which means that the smarts we have attained through our experience have to be revised and repurposed.

––Paul Lynch

After Pedagogy: The Experience of Teaching (xvii)

How might we learn to read, teach, and pedagogically engage with student writing produced in genres, media, and/or digital platforms in which the teacher (and perhaps also the student) lack experience and expertise? In other words, when neither know exactly what they are doing or looking for, when they are still “figuring it out”? Building on what Paul Lynch calls an “after pedagogy,” I (Donna) hope to demonstrate why student writing is one of our most valuable resources for teaching—and learning. Perhaps even more so when we venture away from our expertise of teaching primarily familiar and comfortable print-based genres.

In After Pedagogy: The Experience of Teaching, Lynch suggests that teaching is still possible in a postprocess landscape, but we just need to think about it differently. Rather than pedagogy being the exigence for teaching, pedagogy is that which responds to teaching and follows classroom experience. Lynch is calling for a pedagogy that comes after teaching, or an “after pedagogy.” In this after pedagogy, the question is not about how such and such theory can help us teach our students on Monday morning, or what he calls “the Monday morning question.” Rather, the question we need to ask is: “What do I do on Tuesday morning with the experience of Monday morning?” (xviii).

I want to reframe Lynch’s “Tuesday morning question” slightly: What do we do with the writing that we ask students to produce when we do not yet have a firm conception of what it should look like or do? That is, when we do not have a clear mental image or an “Ideal Text” (Knoblauch and Brannon) firmly implanted in our teacherly brains? What is the value of asking students to work in genres and media that an experienced teacher herself has not mastered? To what extent might the work that students create in genres for which the teacher has little expertise spur her to an “after pedagogy,” where she can continue to “invent” her practice after the fact?

Thirty-five years ago, David Bartholomae wrote that students must “invent the university” and its discourses. They must learn to “speak our language” long before they have acquired the skill to do so (135). He suggests that “the act of writing takes the student away from where he is and what he knows and allows him to imagine something else” (146). Simply put, these students must commit to writing before they have figured it out. “Commit, then figure it out” is the slogan of Mick Ebeling, founder and CEO of Not Impossible Labs. It’s an especially fitting mantra for the invention of digital genres in the era of “electracy” (Ulmer)—both for students and for teachers. Bartholomae continues:

What our beginning students need to learn is to extend themselves by successive approximations into the commonplaces, set phrases, rituals and gestures, habits of mind, tricks of persuasion, obligatory conclusions and necessary connections that determine the “what might be said” and constitute knowledge within the various branches of our academic community. (146)

In many ways, I believe Bartholomae is demonstrating a kind of “after pedagogy” in his essay. However, he is writing about students who are trying to perform in a discourse that the teacher has already mastered, one that the students can only imagine. Let me recast and repurpose Bartholomae’s phrases and sentences by substituting the “experienced teacher” for the “beginning student”:

Experienced teachers need to (re)invent their teaching by asking their students to imagine what might be said and how it might be said in genres for which neither has much expertise or practice. These acts of writing take the student and the teacher away from where they are and what they know and allow them to imagine something else. What our experienced teachers need to learn is to extend themselves by successive approximations, into new commonplaces, rituals and gestures, habits of mind, tricks of persuasion, and necessary connections by studying the writing that their students produce, especially in genres for which the teacher is not the expert.

As a teacher of writing and literacy studies, I have been thinking a lot about what it means to teach writing in an era when literacies continue to accumulate (Brandt) and accelerate (Keller). Writing in 1995, Deborah Brandt suggests that “the ability to use literacy at the end of the twentieth century maybe best measured as a person’s capacity to navigate and amalgamate new reading and writing practices” (651). How much truer her observations are twenty-five years later! The literacy challenge that we face today is not so much the “lack of literacy” as it is the “surplus … Being literate … has to do with being able to negotiate the burgeoning surplus” (666). I teach an upper-division literacy studies course, which is an elective in our Professional Writing, Literacies, and Rhetoric minor. My version of the course requires students to come to terms with a great deal of (new) content. Three years ago, wondering what I could ask students to do that would help them better connect all the concepts and theories into a meaningful conception of literacy for themselves, I decided to have them engage in a quarter-long, content curation project using the infinite, revisable canvas of Prezi Classic. Content curation, which has been called an “emerging” twenty-first century information literacy, can also serve as a practice for students’ own continuous learning. I had read about content curation and witnessed the upsurge of digital content curators on the web, but I had never attempted such work myself. Although I have used Prezi Classic for both presentation and invention, I have no experience or expertise in actual curation. Neither do my students. We are all figuring it out.

Reflecting on “Inventing the University” in an interview with John Schilb in 2011, Bartholomae alludes to the notion that paying attention and noticing what is interesting about student writing does more than just provide a helpful response to the student. It also pushes the teacher to ask: What do I do next? He recounts how his first composition teacher, Bill Coles, would evaluate teachers by asking, “What did this teacher notice in a student essay? What became interesting or important through that noticing? And as a consequence, what should the student and the teacher do next?” (264). In a sense, Bartholomae’s final question about what the teacher should do next prefigures Lynch’s argument in After Pedagogy. Lynch writes, “Our work—literally ‘post’—is to engage that which is occasioned by our students’ work” (xviii). If we attend to the ways students take up and invent these new genres, their texts can lead us to our next pedagogical “approximation.” Our students’ work can make us smarter next time. Lynch’s ideas about after pedagogy suggest a kind of “backward transfer” for teachers. Backward transfer occurs when the learning and acquisition of new knowledge influences the understanding of prior knowledge and experience—or, in this case, pedagogy (Qualley). Such an approach means that we must be willing to commit to asking students to engage in writing projects where we may not yet understand exactly what we are looking for until after we see what they have done. And, of course, students also have to be willing to “commit, before they figure it out,” which is not always easy.

In the next section, Matthew Sorlien, a fourth-year undergraduate student, talks about the Prezi curation that he created for my course in the fall of 2018. I am intrigued by Matthew’s project because of the way he infuses his presence and perspective throughout his curation with the insertion of multiple “What I’m Thinking” slides. He comments on the material and reflects on the process of curation and connection-making itself. He creates a roller coaster of a path, zig-zagging back and forth through the material, quickly shuttling back to concepts to remind viewers of a connection to a previous slide. And, unlike many of the projects that I receive from students, Matthew’s final path does not simply adhere to the order in which the material was introduced in class or the order in which he added it to Prezi. His process, as he explains below, is recursive as well. While other students’ projects may have been more elegant, concise, and streamlined by design standards, Matthew entangles thinking asides and meta-commentary with the subject matter, giving his Prezi an essayistic feel. Because Prezi is meant to be viewed online, it is difficult to represent his work in a two-dimensional format. For example, we are not able to capture the forward and backward movement which is one way that this genre makes meaning. We have, however, included a link to Matthew’s actual Prezi in the Works Cited page for interested readers.

Matthew Sorlien: The Value of Playful, Happy Accidents

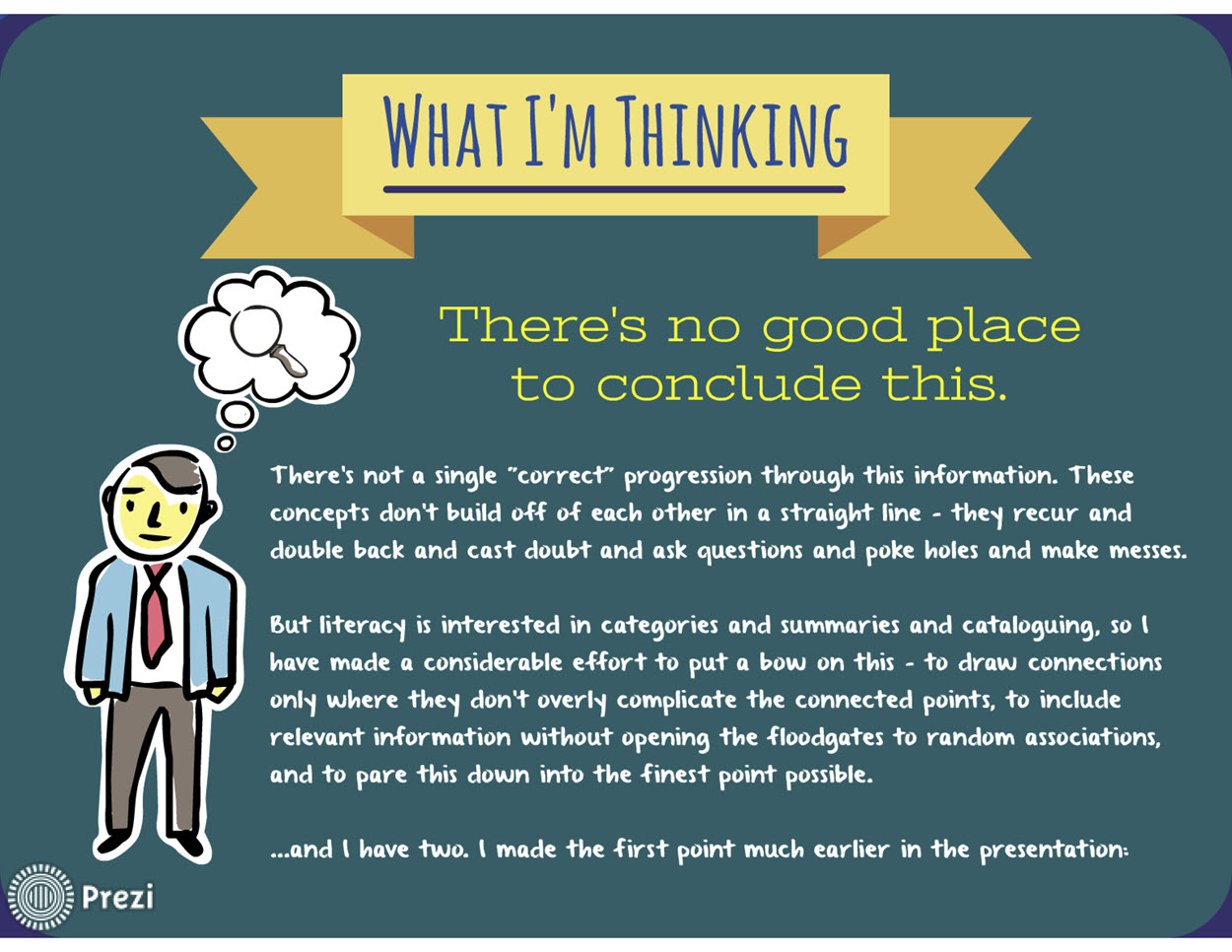

From a traditional “academic” standpoint, my curation project probably falls short. It has a chaotic appearance, and its spatial organization is often at odds with the “path” through the slides (see Figure 1). It has an absurd number of arrows, many of which don’t seem to communicate anything in particular. And, perhaps most notably, it has no argument, and I didn’t try to retroactively impose one onto it at the end. Rather, the path concludes with the frank admission that there is “no good place to conclude this” (Figure 2). It would not be a very successful school essay—but it is a pretty good Prezi, largely because I started to goof off while making it.

Figure 1. Matthew’s Prezi curation.

Figure 2. There’s no good place to conclude.

The idea of “play” was important to the creation of this Prezi long before I realized it would be. The first thing I noticed about the Prezi as an assignment was the ambiguity involved—no one knew what a “proper Prezi” was supposed to look like. At first, I found myself building a huge collection of ideas without knowing what I was going to do with them. Because I was working without a rigid template, I began to follow threads as they emerged without stopping to worry about where they would end. I used class time to play around with the design. I grabbed a photograph of James Paul Gee along with all the quotes I thought might be interesting, and then meticulously arranged them all into slides I’d lined up on his teeth. I spent nearly a full day using goofy clipart of animals holding cigarettes to represent some of the field’s big thinkers. It’s fair to say that because I didn’t know what I was doing, I started messing around. The practice of incorporating play into my work eventually became interesting and thematically appropriate, which my high school art teacher would have called a “happy accident.” I stopped wondering about whether my work was any good, or even whether it might lead to something good. The value in what I was doing was simply the fact that I enjoyed doing it.

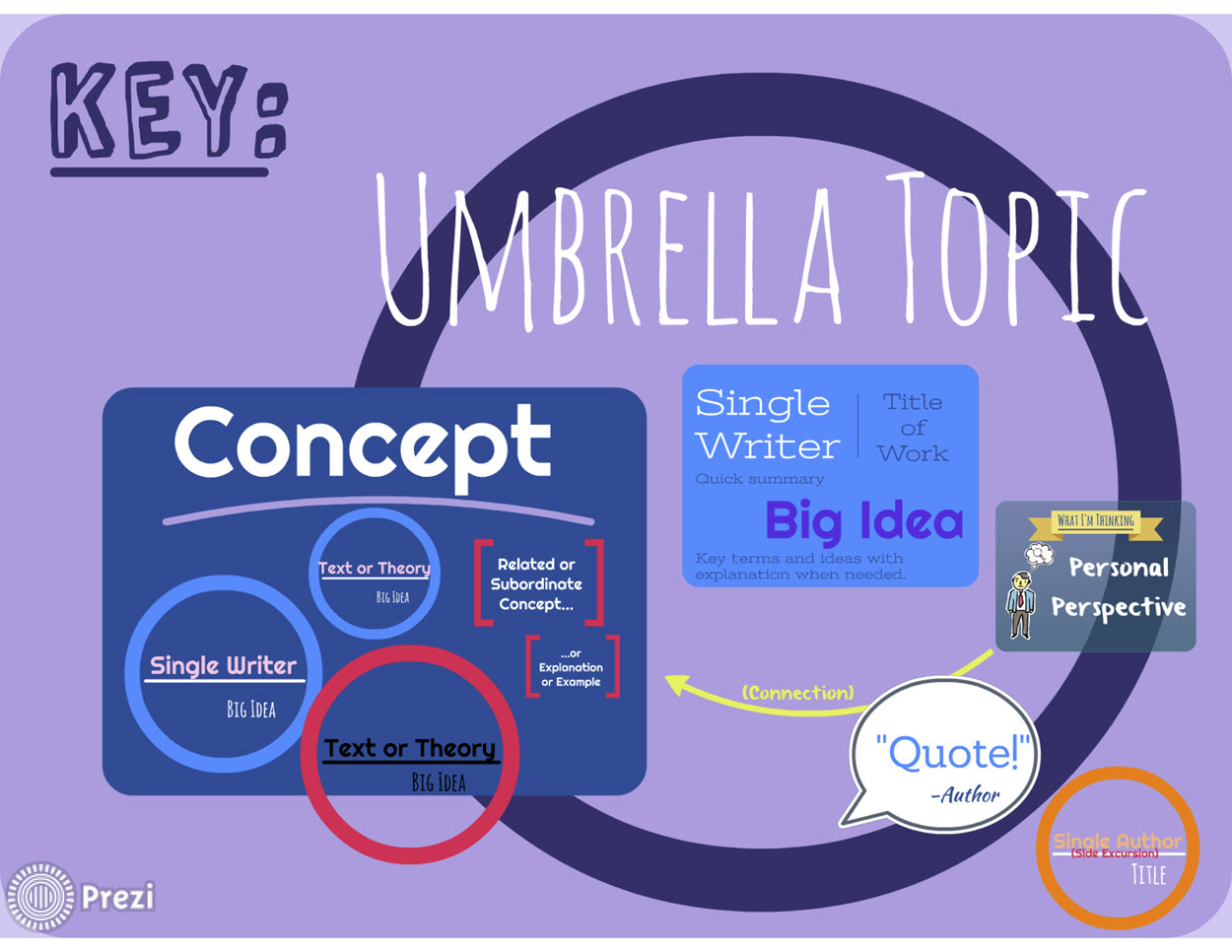

I continued writing for fun, rarely slowing down to revise anything for most of the course. The design followed a similar pattern, growing from a lot of little decisions and adjustments in response to how the material seemed to be developing for me over the quarter. The assignment called for a key, and while I could have started with the key to help me keep everything organized for the next ten weeks, I didn’t end up creating it until everything else was mostly done. The key that emerged (see Figure 3) wound up describing rather than dictating the Prezi design. Any organizational principles that seem to show up in the design were unintentional or unconscious—more happy accidents.

Figure 3. Matthew’s key.

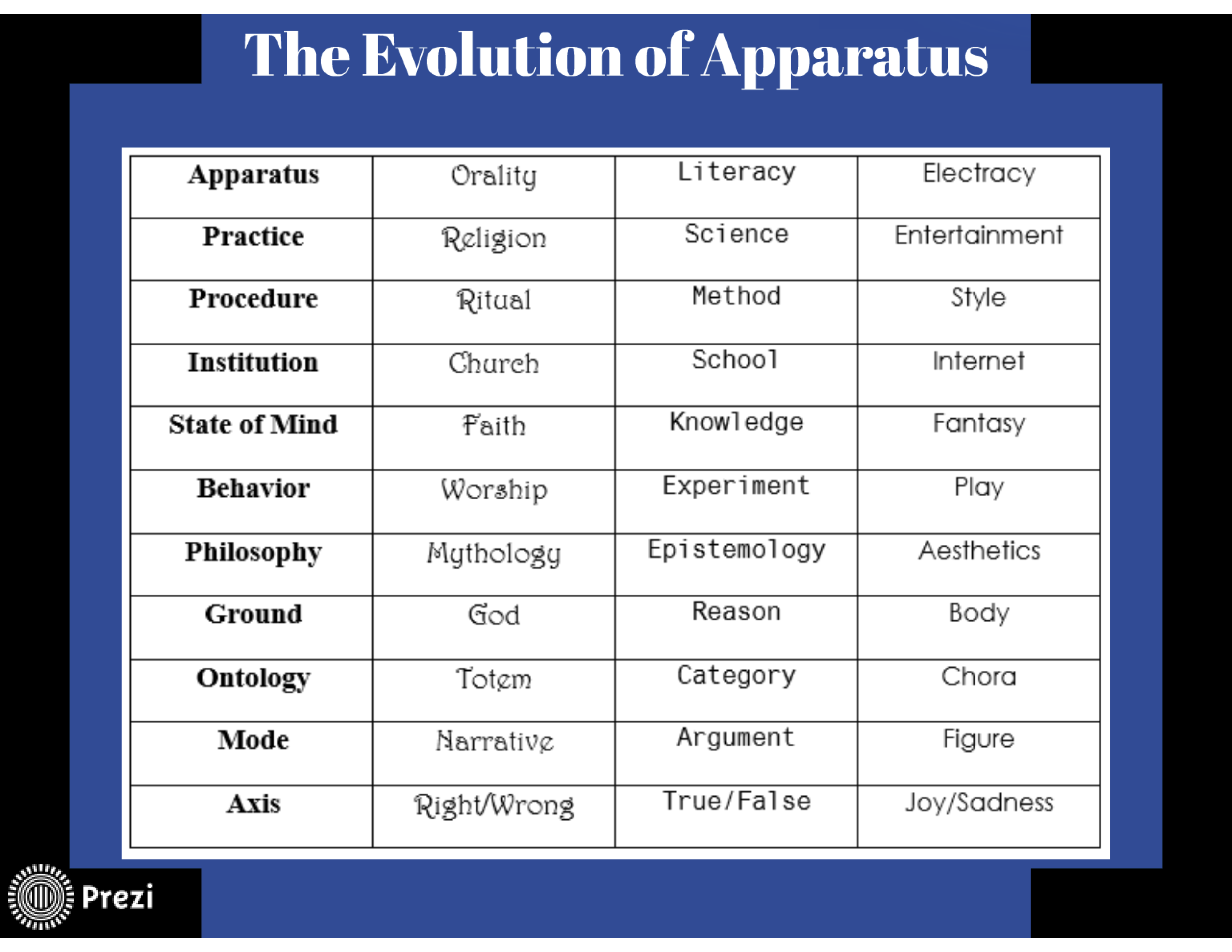

Later in the course, we were introduced to Gregory Ulmer’s concept of electracy. As I began working this concept into the Prezi, it changed the way I was thinking about what I had done so far. I created a slide of Gregory Ulmer’s apparatus table comparing the attributes of electracy with those of literacy and orality (See Figure 4). Seeing the behavior of “play” in the electracy column enshrined alongside “experiment” in the literacy column legitimized the notion of play as a way to make meaning. Perhaps play could even be part of scholarly work. I began to realize that the lack of a blueprint for this project meant that what makes a good, scholarly Prezi was negotiable.

Figure 4. Gregory Ulmer’s apparatus table.

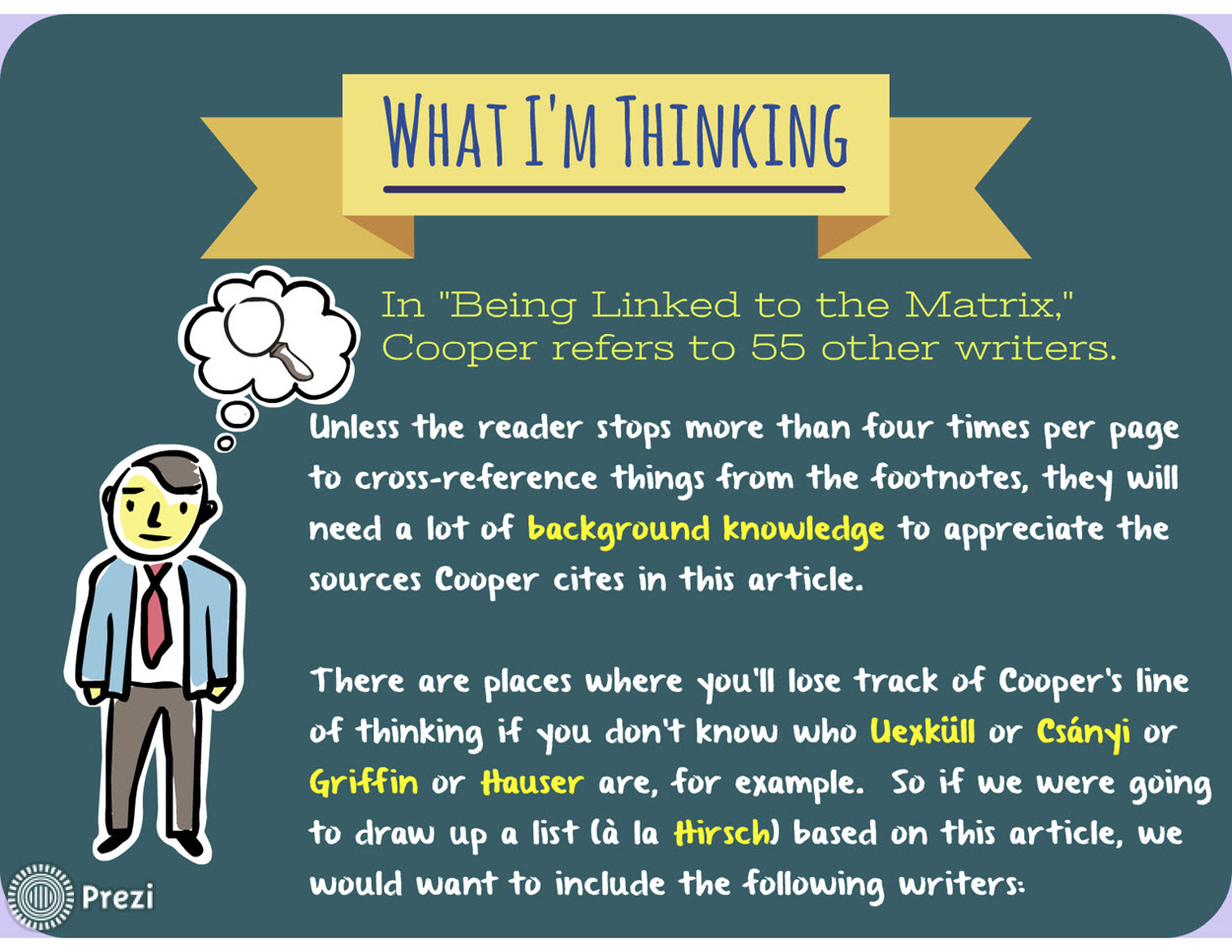

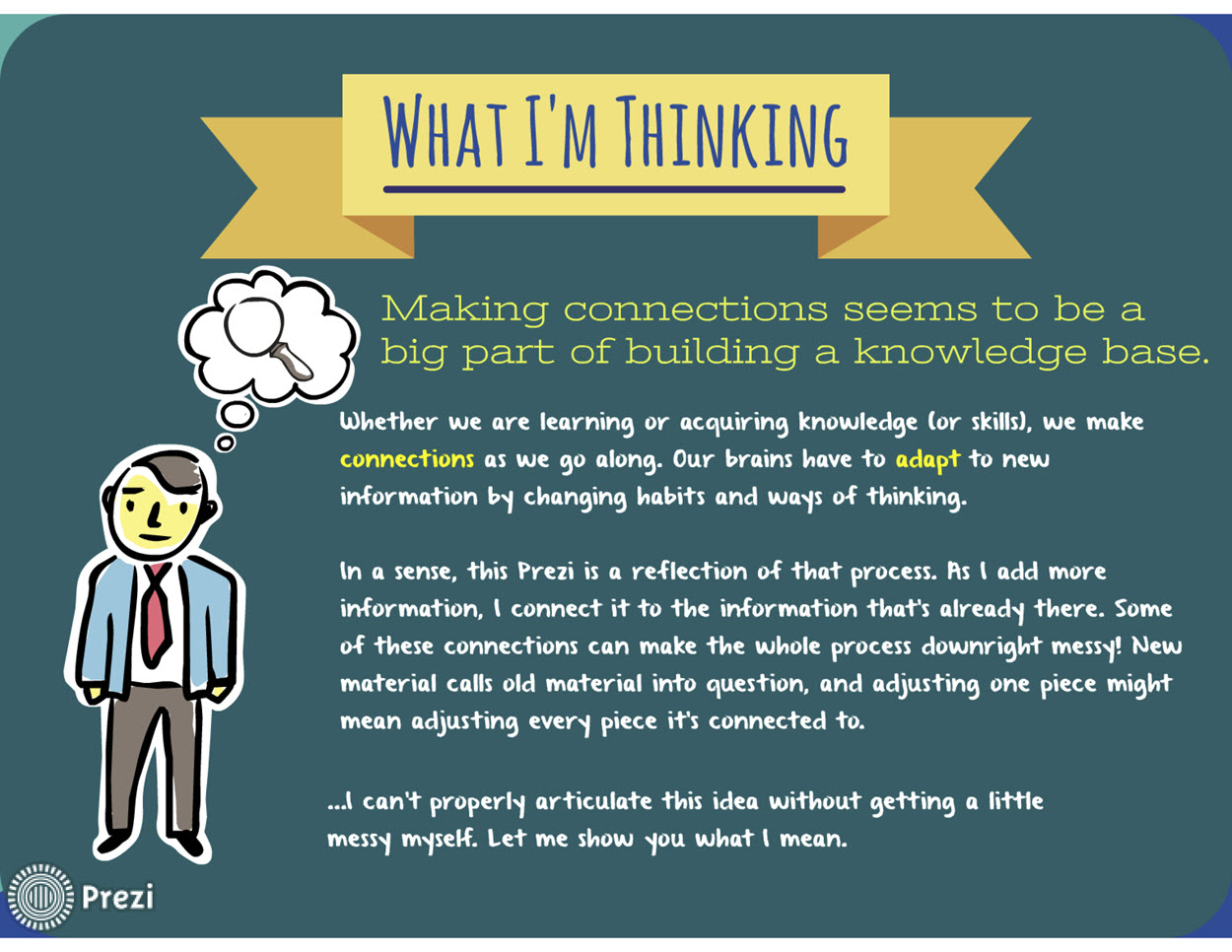

The wiggle room that I allowed myself was helpful when I wanted to generate content, but I felt a lingering tension over what to do with that content. I still couldn’t answer basic questions about my purpose for writing. Who exactly was I writing this thing for, and why was I telling them all this stuff? To be able to organize and deliver the considerable mass of course material without being squashed by academic nihilism, I pretended that I was constructing the project for other reasons, for someone else, and maybe even as someone else. The “What I’m Thinking” (WIT) slides diverted me from the forward progression of Prezi and allowed me to address and navigate the awkward rhetorical position between writer and audience in this assignment. These diversions allowed me to present myself authentically within the work—not as a disembodied voice faking expertise, objectivity, or even comfort, but as a writer still trying to make something out of the material, even though they aren’t sure what that something is. Normally, I wouldn’t be comfortable interrupting what I am writing about to directly address my difficulty with writing. But the WIT slides became my response to the rhetorical tension I felt about writing outside of my expertise with this project.

In the WIT slides, I personified myself as the writer through clip art, which would probably not be well-received in a traditional essay. The background color and font choice create a “teacherly” chalkboard aesthetic, partly to draw attention to the weirdness of the rhetor/audience relationship and lampoon the idea of instructing the person who had introduced me to all the material. I created the first WIT slide out of frustration with the project, and by another happy accident, that gave me a format that allowed me to own my role as the writer.

I ended up making nineteen WIT slides, which is roughly 10% of the total slide count and well over 10% of the word count. When I got stuck curating information, which happened fairly often, I started reflexively pivoting to WIT slides. Sometimes a WIT slide would end up reaching something like a conclusion, but that was rarely my initial goal for them. I used them to make interesting but probably inconsequential observations (see Figure 5), or to ask questions I didn’t particularly care to answer (see Figure 6), or to hint at a possible link to something in the real world (see Figure 7).

Figure 5. WIT slide: Inconsequential observations.

Figure 6. WIT slide: Questions I didn’t care to answer.

Figure 7. WIT slide: Link to the real world.

My favorite WIT slides, though, are the ones I wrote for no discernable reason apart from self-amusement. For example, the WIT slide in Figure 8 wasn’t originally meant to express much other than the fact that Nicholas Carr reminded me of Ian Malcolm from Jurassic Park. I included that slide in the Prezi because I thought it might be slightly funny to someone who had read Nicholas Carr’s “Is Google Making Us Stupid?” and liked Jurassic Park. Later, I added a small list of other writers whose work seemed relevant to Carr’s writing on neuroplasticity, which is potentially more fruitful (and probably more scholarly) than the Jurassic Park reference. But the point of the slide was that it was funny, and I kept it purely for my own pleasure.

Figure 8. WIT slide: For self-amusement.

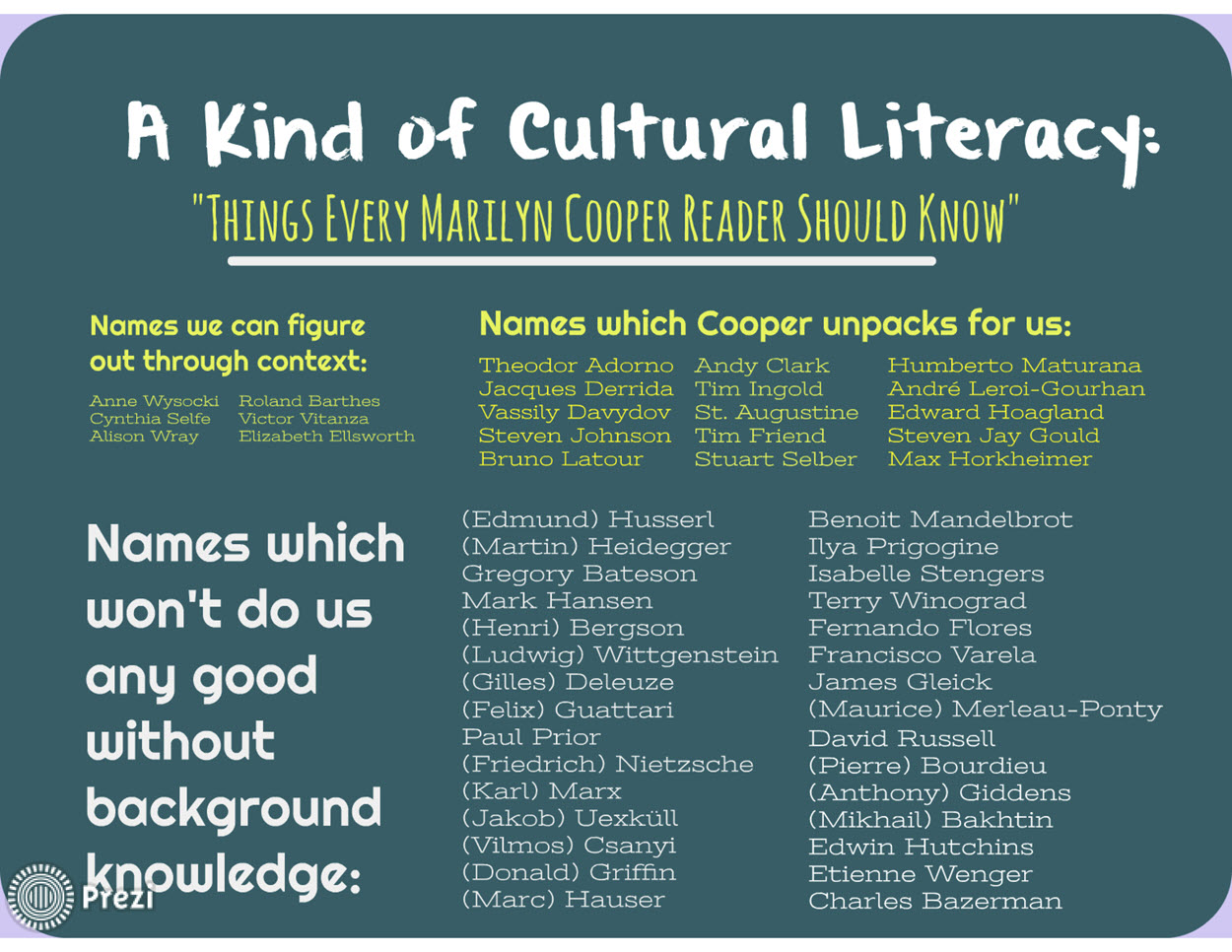

Play was also how I got up the nerve to comment on stuff written by people smarter than me. I felt comfortable working through most of the texts that I was curating for the Prezi project, but Marilyn Cooper’s “Being Linked to the Matrix” resisted all my efforts to gain a foothold. One day, I gave up trying to understand it and, instead, spent the entire class period composing a list of all the references she uses that went over my head. I had no intention of looking any of them up. I was just being petty.

A few days later, I gave Cooper another shot (see Figure 9). I looked up all of the names I’d compiled and organized them according to how hard it was for me to understand what they were doing in Cooper’s article (see Figure 10). Rather than working to make sense of the material, I was chasing down what was interesting to me. Eventually, that process acted as a springboard into rewarding mental work. More importantly, “play” had somehow enabled me to assume equal footing with the intimidating Cooper and write without critiquing myself.

Figure 9. WIT slide: Background knowledge and Marilyn Cooper.

Figure 10. Categories of sources in Marilyn Cooper.

This project owes much of its strength and novelty to playful, happy accidents. While screwing around may not be what Brandt had in mind, it surprisingly expanded “my capacity to navigate and amalgamate new reading and writing practices.” By the end, I had negotiated a good, scholarly Prezi, though I couldn’t pinpoint where play ended and scholarly work began.

Student Writing: An Essential Resource for After Pedagogy

Matthew’s Prezi contains 205 slides, including the nineteen WIT slides (see Table 1). I have highlighted those slides that appear in this chapter. His first WIT slide (50) appears after he has already discussed the following information: curation (slides 3-16), discourse (slides 17-22), primary and secondary discourses (slides 23-24), participatory culture (slides 25-27), affinity spaces (slides 28-33), the differences between discourses and affinity spaces (slides 34-37), the differences between learning and acquisition (slides 40-44), early borrowing (slide 46), and the imposter syndrome and the Dunning-Kruger effect as barriers to literacy (slides 47-49).

Table 1. Matthew’s collection of WIT slides.

|

Slide Number |

Title and Topic |

|

50 |

Making connections seems to be a big part of building a knowledge base. |

|

55 |

Relative weight of size of words in a word cloud. |

|

60 |

Conceptual Darwinism: curation is no longer a Pinterest board - it's an open bookmarks folder with a finger on the "delete" key. |

|

61 |

Conceptual Darwinism (Take II). "Curation" is knowing when to kill good ideas so that better ideas have room to breathe. |

|

96 |

Image Management: Tellability is primarily relevant to dominant discourses. |

|

97 |

One reason that critiquing a dominant discourse is a bi-discoursal skill. |

|

112 |

More on the later: Sticking a pin in Karl Greenfeld for now, or cultural literacy came down on the wrong side of Janks’ "access paradox." |

|

141 |

If Carr were played by Jeff Goldblum: “I keep thinking back to neuroplasticity.” |

|

156 |

Is Greenfeld’s “Faking Cultural Literacy” self-satire? |

|

168 |

Ong says, "You can know how to use grammatical rules. . . without being able to state what they are." |

|

175 |

Leonard Shlain's ideas match the tone of literacy crisis texts, but focuses on the lost benefits of orality. |

|

185 |

What the hell happened in 2016? The American political system has passed the tipping point into electracy. |

|

196 |

Hey, remember acquisition? Developing knowledge through play sounds like acquisition to me. |

|

197 |

Marilyn Cooper weighs in: Animals show a gap in the conceptual bridge from acquisition to play. |

|

199 |

In "Being Linked to the Matrix," Cooper refers to 55 other writers. |

|

200 |

A kind of cultural literacy: “Things every Marilyn Cooper reader should know.” |

|

201 |

There’s no good place to conclude: I have two points, the first I made earlier. |

|

202 |

Conceptual Darwinism (Take II): (Returns to slide 61) |

|

203 |

And one last thing: Seemingly clean, standalone ideas are often just poorly-contextualized ideas. |

Matthew’s first WIT slide (see Figure 11) in his path focuses on the messiness of the curation process using concepts he has previously defined: “Whether we are learning or acquiring, we make connections as we go along.” He continues: “The problem is that “new material calls the old material into question and adjusting one piece might mean adjusting every piece it’s connected to.” Unlike the relative ease of copy and paste or add and delete revision practices that students typically use in print-based literacies, revision in Prezi can cause a domino effect—rework or remove one piece, and the whole thing can come tumbling down.

Figure 11. Making connections while curating information.

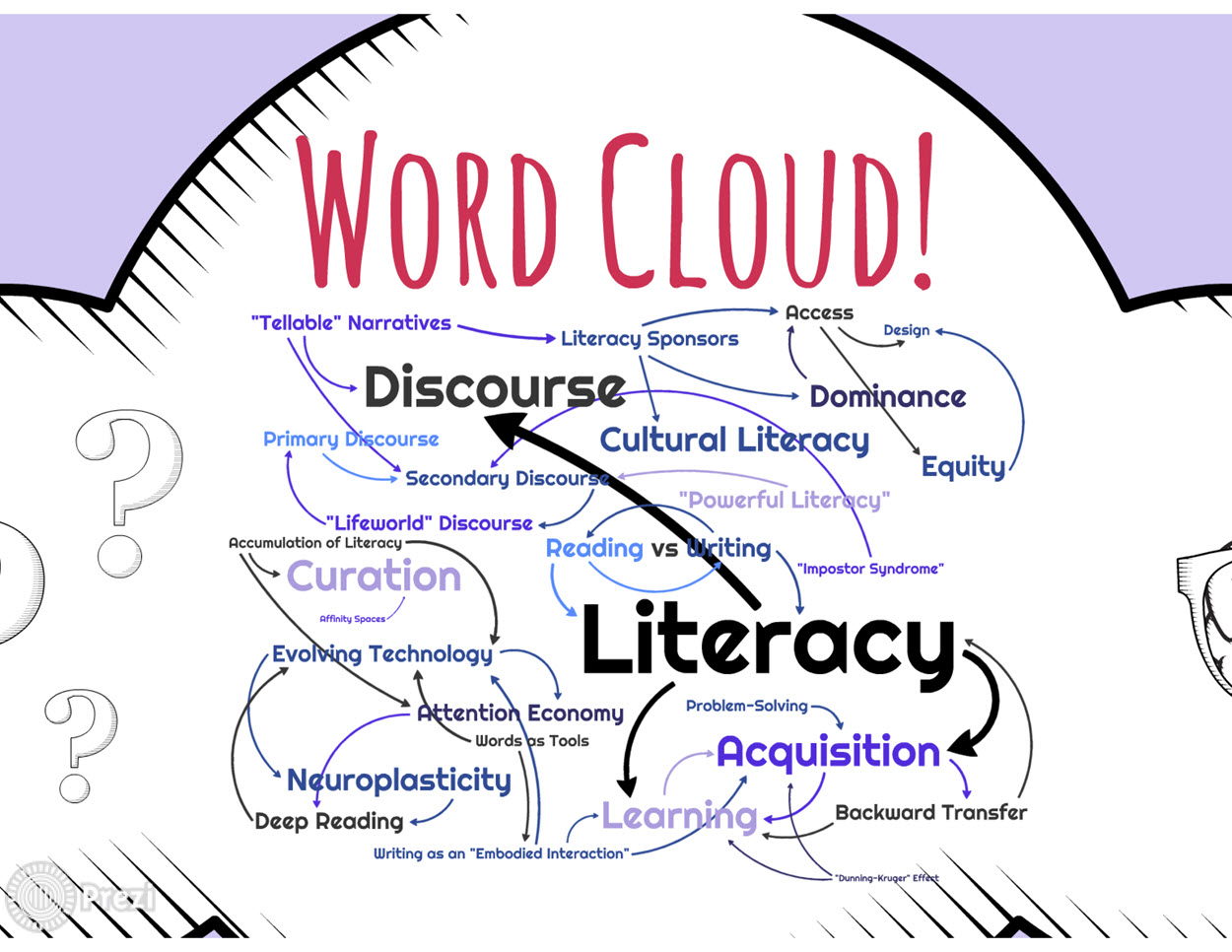

Matthew comments on this problem again in a subsequent WIT slide when he notes why he didn’t update a Word Cloud slide of concepts that he made earlier in the quarter (see Figure 12). He writes:

I couldn't properly update it just by adding to it. I would need to change the size of several terms to reflect shifts in relevance. The sheer volume of information and the multitude of connections between concepts would make it impossible to change just one thing. This difficulty helps illustrate the recursive nature of learning.

The difficulty also demonstrates the recursive nature of learning via backward transfer, a process that I attempt to activate with these projects to deepen students’ understanding of the material. Yet, the ever “burgeoning surplus” of information in this course lends itself to unruliness as students find themselves veering off a linear path—unless, like Matthew, they can eventually turn their position of student into that of playful writer and curator.

Figure 12. Word cloud of concepts.

Shortly after Matthew discusses his word cloud, he pauses to reflect on his changing thinking about the process of curation itself. In a WIT slide that he titles “Conceptual Darwinism” (see Figure 13), he suggests that curation is a “tool for pitting ideas against each other so that only the strongest and most relevant idea survives. So, for me, curation is no longer a Pinterest board—it’s an open bookmarks folder with a finger on the "delete" key.” His next slide in the Prezi (not shown here), called “Conceptual Darwinism (Take II),” contains a single sentence: “‘Curation’ is knowing when to kill good ideas so that better ideas have room to breathe.” Indeed!

Figure 13. Conceptual Darwinism.

Matthew has helped me to articulate both the promise and the problem of this curation project and my pedagogical assumptions that inform it. Many students, I now realize, continue to treat the project like a “Pinterest Board.” They pin all the ideas, concepts, theories, and examples from the course to their Prezi Canvas, regardless of how they connect to or negate previous pins or make them obsolete or unnecessary. When they do find a way to be playful, it is usually through design. Matthew, on the other hand, plays with the material itself. His WIT slides could more accurately be retitled, “What I’m playing around with” slides. He frequently takes what I might call a heuretic approach. For example, instead of showing what he makes of Cooper’s fifty-five different sources (Figures 9 and 10), he demonstrates what he makes from these sources. Reiterating Gregory Ulmer’s point, Sarah Arroyo reminds us that “heuretics focuses on “production” and is not “tied to the notion that in order to teach and learn something, we first have to master it” (112). While I have no expertise in the genre of curation, I realize now that I do have knowledge of the material I am asking students to curate—and as Matthew notes, students know that. I suspect that for many, the curation project became a kind of cultural literacy test where they attempt to demonstrate knowledge of what “every literacy student should know,” using a pleasing and engaging design.

If I had space in this chapter, I could probably categorize my students’ projects along the lines that Bartholomae undertakes with student placement essays at the end of “Inventing.” Similar to what Bartholomae finds, the more interesting projects are those that do something other than create an aesthetically clean and elegant design or construct an accurate and comprehensive Pinterest Board. The student projects that most compel my Tuesday morning questions are the ones that are filled with rabbit trails and playful meta-asides like Matthew’s. My sense of what and how these projects might become (as opposed to what they should be) only emerges after seeing what my students do, rather than from any expertise I have beforehand. The first time I attempted curation projects in 2016, three students created a key for their projects. One of my next “approximations” the following year was to make “keys” a requirement for the project. Matthew’s key in Figure 3 deviates from other students’ keys in that he made it after his Prezi, and it does not appear as a linear list. Instead, it serves to foreshadow the layout and design of the Prezi itself for readers. Matthew shows me how this project lends itself to the kind of invention and play that leads to happy accidents—for his learning and for my pedagogy.

Asking students to commit to making something before they figure it out—indeed, before the teacher herself has figured out the implications and possibilities of what she is asking— might also be understood as a heuretic pedagogy under the apparatus of electracy. Here, making and doing typically proceed knowing. The pedagogies for teaching and learning writing in the era of electracy are still being invented, and student writing lies at the center of this invention. As Ulmer notes, student work is “helping to invent the future of writing” (7). Students and their writing become an essential resource for making all of us smarter next time, and not just in the classroom.

Coda: What Comes after the “Tuesday Morning Question”?

We can collaborate with students to invent and evolve the discipline itself. Writing in 1997, Joseph Harris suggested that composition is a “teaching subject … which defines itself through an interest in the work students and teachers do together” (ix, emphasis added). The work students and teachers do together need not be limited to the Monday or Tuesday morning pedagogical questions. Indeed, the Wednesday or Thursday or Friday questions might be the ones that can move us out into the larger public of our field. These are the questions that compel students and teachers to continue “figuring it out” together in the chapters of books, pages of journals, and panels for conferences. As Matthew and I suggest in Figure 14, when we move away from scholarship that focuses exclusively on what teachers make of student work to projects that explore what teachers and students can make together with student work, we can expand the field’s focus on student writing, but this time we don’t leave the student out of the equation.

Figure 14. What we’re thinking.

Works Cited

Arroyo, Sarah. Participatory Composition: Video Culture, Writing and Electracy. Sothern Illinois UP, 2013.

Bartholomae, David. “Inventing the University.” When a Writer Can’t Write: Studies in Writer’s Block and Other Composing Problems, edited by Mike Rose, Guilford, 1985, pp. 134-165.

Bartholomae, David and John Schilb. “’Inventing the University’ at 25: An Interview with David Bartholomae.” College English, vol. 73, no. 3, 2011, pp. 260-282.

Brandt, Deborah. “Accumulating Literacy: Writing and Learning to Write in the Twentieth Century.” College English, vol. 57, no. 6, 1995, pp. 649-668.

Harris, Joseph. A Teaching Subject: Composition Since 1966. New ed., Utah State UP, 2012.

Keller, Daniel. Chasing Literacy: Reading and Writing in the Age of Acceleration. Utah State UP, 2014.

Knoblauch, C.H. and Lil Brannon. Rhetorical Traditions and the Teaching of Writing. Boynton/Cook, 1984.

Lynch, Paul. After Pedagogy: The Experience of Teaching. CCCC, 2011.

Qualley, Donna. “Building a Conceptual Topography of the Transfer Terrain.” Critical Transitions: Writing and the Question of Transfer, edited by Chris M. Anson and Jessie L. Moore, Parlor Press, 2017, pp. 69-106.

Sorlien, Matthew. “Studies in Literacy.” Prezi Classic, 2018. prezi.com/xqznyzygv4cg/?token=c41afef401075372f43e5f374a2e81bf675e46999cfe9a267734e6ff2abe39f2&utm_campaign=share&utm_medium=copy.

Ulmer, Gregory. Internet Invention: From Literacy to Electracy. Longman, 2003.